Reflections on curiosity, stubbornness, and translating hope through automotive metaphors

I didn’t sit down to write a position statement. I sat down to sort through my own work, and found myself reflecting on how often engagement has less to do with the idea itself, and more to do with the language used to introduce it.

Today turned into a reflective one as I found myself collating resources I’ve created over the past few years. It’s a process that often reveals patterns I don’t notice when I’m busy “doing”.

One moment that resurfaced came from 2021, during a breakout session in a Hope-Action Theory webinar. Someone commented that while the framework was interesting and valuable, it probably wouldn’t land with certain client groups, such as first responders or people working in the mining industry.

Their reasoning was that the language used, and the pinwheel metaphor, felt too abstract.

It was a fair comment.

But it also made me curious… and, if I’m honest, a little stubborn.

I found myself wondering whether this was genuinely a limitation of the framework, or whether it reflected something else. Perhaps unconscious bias. Perhaps narrow probability thinking. Perhaps assumptions about who certain ideas are “for”.

I’d seen similar reactions before when introducing creative engagement strategies with veteran groups. Responses ranged from curious interest, to polite scepticism, to outright rejection (“nope… this sounds like hippy sh*t” 💩).

What helped shift perceptions wasn’t changing the strategy itself.

It was changing the language.

When I began explaining ideas using military language, metaphors, and lived reference points, the same concepts suddenly felt more familiar, practical, and usable. Nothing about the underlying thinking had changed. The translation had.

Around the same time, I had started using automotive language with REME / RAEME veterans to help them articulate transferable skills and strengths. That experience stayed with me. So rather than accepting that some frameworks “just don’t fit” certain groups, my curiosity (and stubbornness) kicked in again.

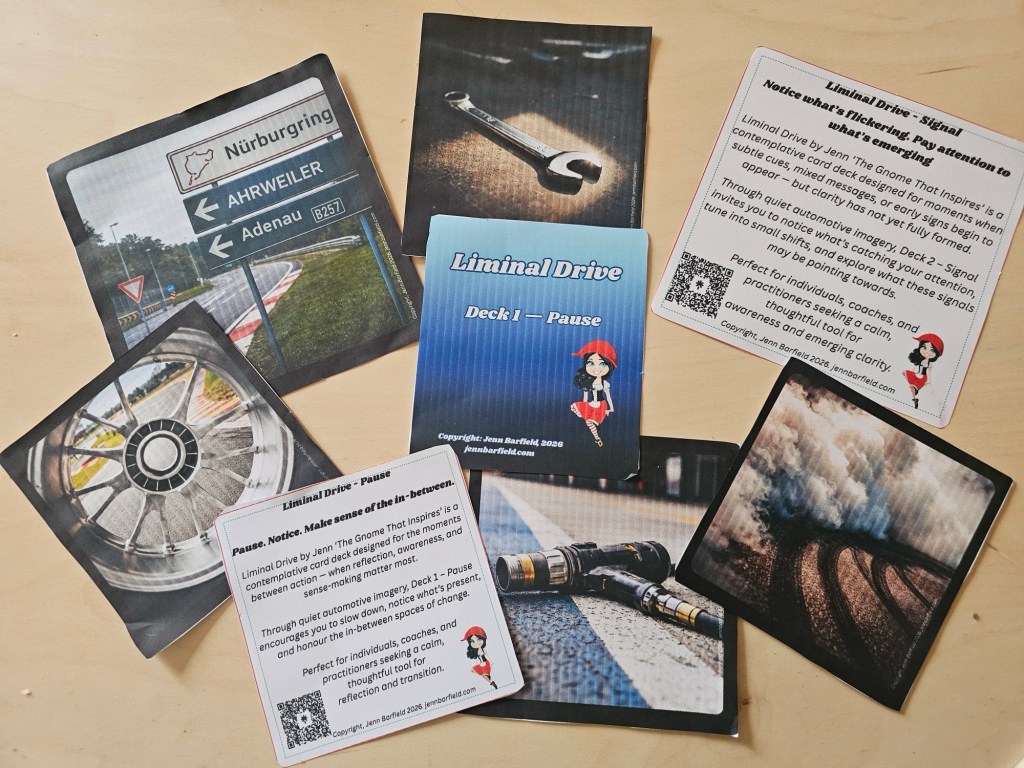

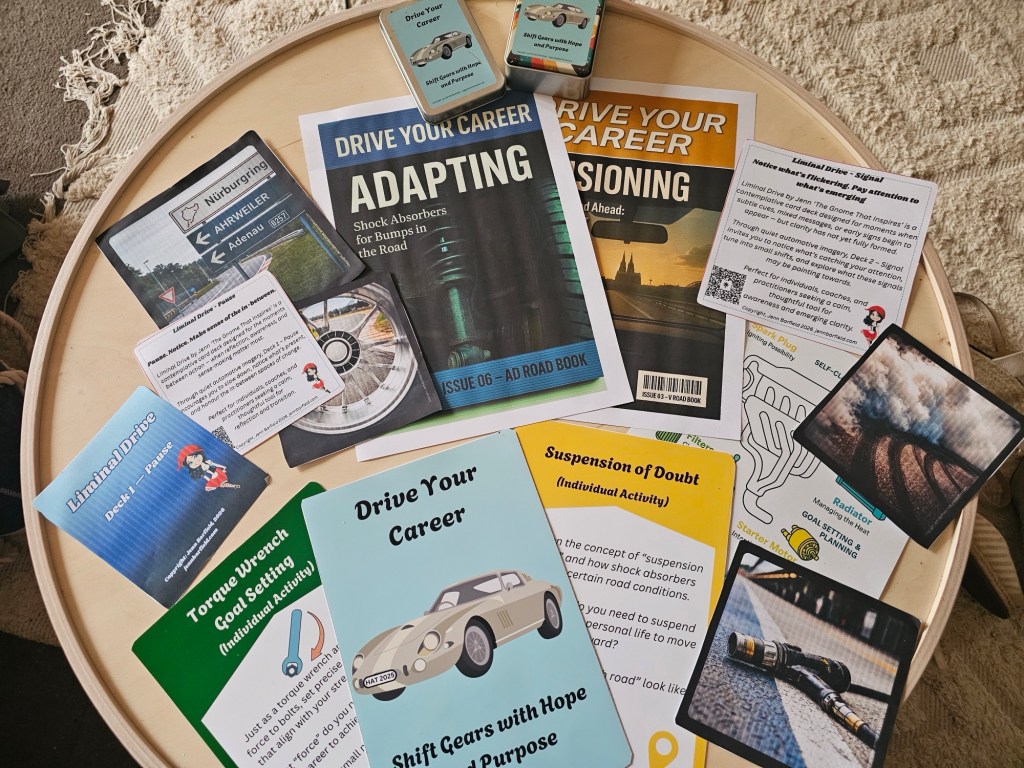

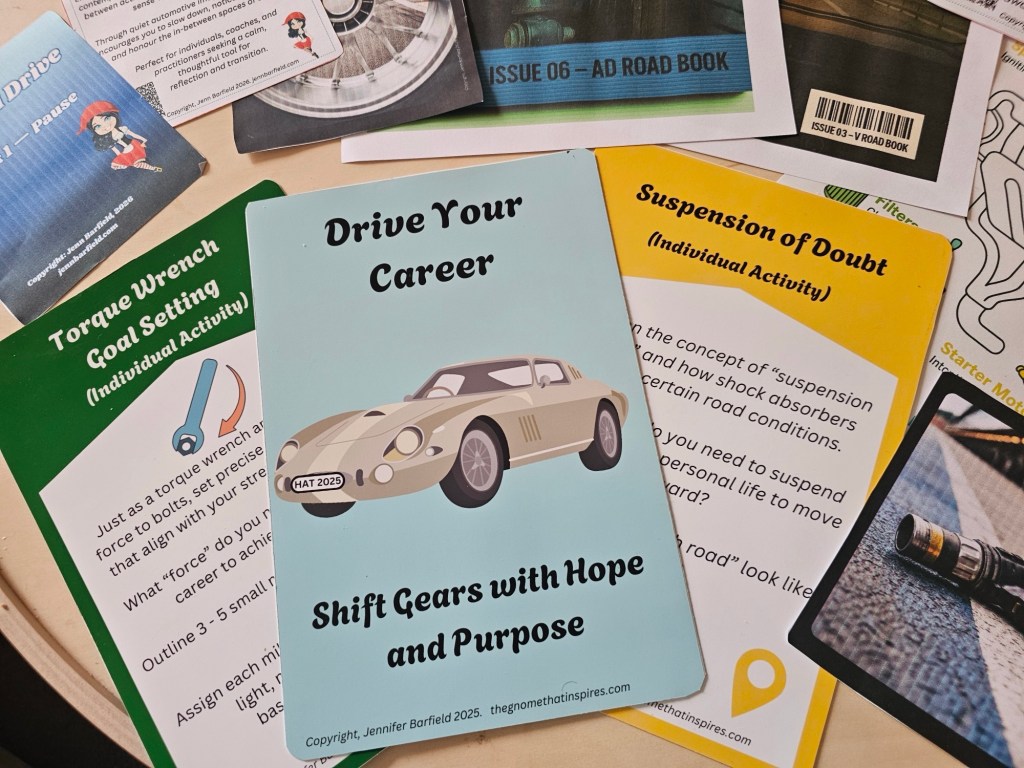

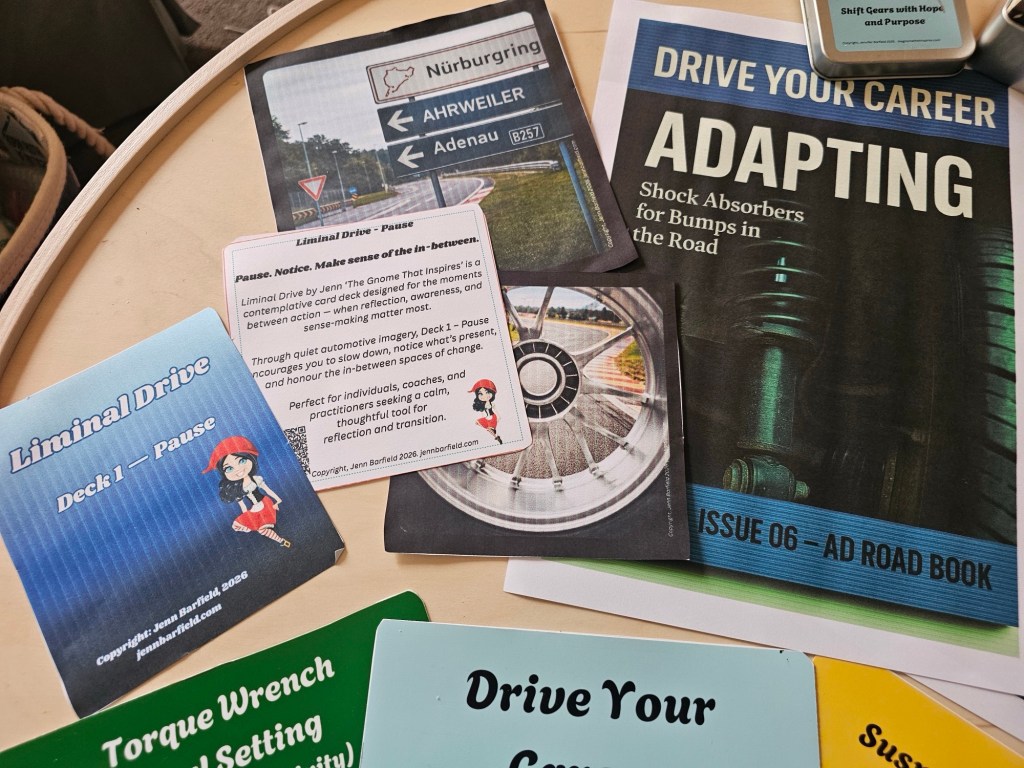

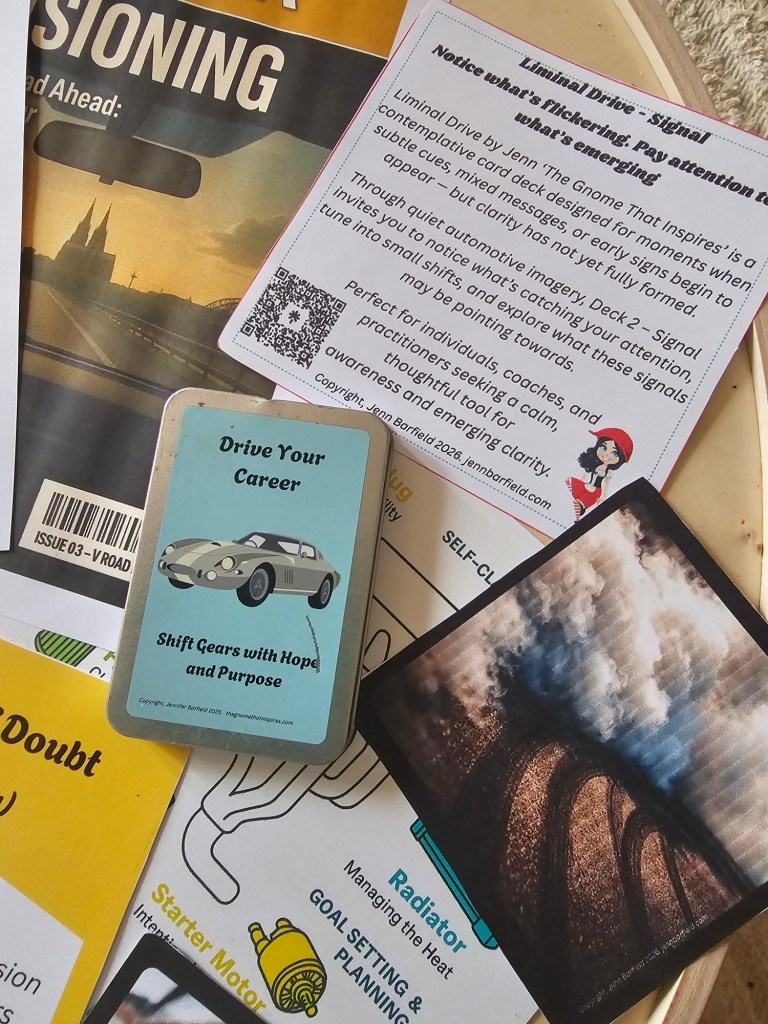

Over the last five years, I’ve continued to research and develop frameworks and resources that draw on language and themes from the automotive industry and motorsports, grounded in Hope-Action Theory and creative engagement strategies.

The intention has always been the same.

To help individuals and teams get curious, spark ideas, stretch their box thinking, and get unstuck.

And from there, to move toward possibility thinking, sustainable hope, and happiness.

That work hasn’t always been easy. It has meant spending a lot of time learning, and continuing to learn, technical automotive language and motorsport contexts. It has involved listening, asking questions, and being willing to sit in unfamiliar territory. But that effort matters.

Not because cars are the point.

But because familiar, concrete language helps people make sense of complex ideas such as self-reflection, clarity, visioning, adaptation, and problem-solving. Language can act as a bridge between lived experience and new ways of thinking, especially in environments where abstract or therapeutic language may feel alien or unhelpful.

Looking back, I realise I was doing this instinctively years ago when teaching young children. In a classroom, if your language doesn’t land, meaning doesn’t either.

And anyone who has ever taught a room full of five- to seven-year-olds knows exactly what happens next.

Chaos. Noise. A classroom running amok.

The lesson has stayed with me.

What happens when we stop asking whether people will “get” an idea, and start asking how we might translate it?